The recommended vaccination schedule for children starts already when the baby is newborn. As a parent, the sheer number of vaccines can be a bit overwhelming and worrying.

Let’s go through the vaccines that are recommended for babies and toddler, when they are sceduled and what diseases they protect against.

Vaccination side effects and common questions can be found in this article.

What Vaccines do Babies and Toddlers Get and When

There are a number of vaccines recommended by the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) to keep children safe and healthy.

These vaccines are administered during the first two years of life because of a higher risk of contracting the illnesses they prevent. Also, the maternal antibodies transmitted in utero decrease by six months of age. It is, therefore, important for infants to receive additional protection.

This includes immunity against viruses such as measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (aka chickenpox). Other vaccines protect infants against serious bacterial infections that can occur during the first three months of life (source). Full immunity, however, does not develop after a single vaccine dose.

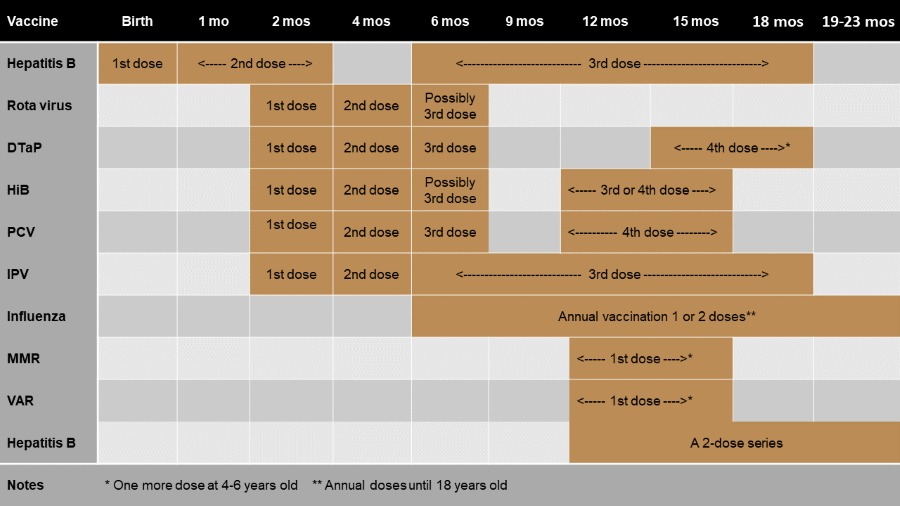

The following chart details the current vaccine schedule for infants and toddlers (reflecting the CDC immunization schedule for 2021):

Pediatric Immunization Schedule for Babies and Toddlers

Catch-up immunization for children that missed the scheduled time occurs between scheduled doses and after the last dose. Discuss the timing with your child’s healthcare provider.

If you plan to travel internationally, it is possible for the baby to receive the 1st MMR and Hepatitis A doses already from the age of 6 months. This too should be discussed with a doctor.

The Vaccination Schedule for Children – the Vaccines and Diseases Explained

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is a virus that can cause a lifelong infection that inflames and damages the liver. Most cases are transmitted from mothers to infants in utero, and during the birth process. For this reason, the WHO has instituted a global initiative for the administration of the hepatitis B vaccine during the neonatal period.

Three doses are necessary for full immunity. Most infants receive a first dose before discharge from the hospital or birthing center. If not, it is given at the first doctor visit. The second dose can be given at either one or two months old, but the last dose is given at age six months.

Rotavirus

Rotavirus is a viral infection in the gastrointestinal tract, affecting the stomach and the intestines. Although people of any age can contract this infection, it is particularly difficult for infants.

Over 200,000 infants and children die from rotavirus each year.

These infections are characterized by profuse vomiting, and several episodes of very foul-smelling diarrhea. Because of the large fluid losses, it is difficult for infants to feed enough to remain hydrated. Hospital care is often needed to provide IV fluids, and support the infant until the infection resolves.

The vaccine against rotavirus is given orally and is a live vaccine. There are two versions, one given at two, four, and six months old, but the other only at two and four months old. If there is a delay in receiving this vaccine, the first dose can be given at 15 weeks old, but no further doses after the baby is eight months old.

If anyone in the home has a compromised immune system, this vaccine should be discussed with your pediatrician before it is administered.

DTaP (Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis)

Diphtheria

Diphtheria is a bacterial infection that starts with a fever and sore throat, but progresses to the formation of a thick coating in the nose and throat that makes breathing difficult. This bacteria also releases a toxin that damages other organs of the body.

While it has been eradicated in many developed nations, the WHO reports at least 16,000 cases per year.

Tetanus

Tetanus, also known as “lockjaw,” is another a bacterial infection. It occurs during injury to the skin such as a soil-contaminated wound or a puncture with metal. It can also develop during the first week of life if a birth occurs in unsanitary conditions.

This bacteria releases a toxin that affects the nerves at the point of skin injury, then spreads to the all of the nerves of the body. As a result, all of the infant’s muscles contract at the same time, causing pain, spasms, and feeding difficulties.

About 38,000 people die from tetanus each year, and half of them are under the age of five.

Pertussis

Pertussis is a bacterial infection, often called “whooping cough” because of the loud sound made while taking a breath prior to coughing. Infants, however, may not express this characteristic sound, and instead gasp for air or stop breathing.

Globally, there are over 150,000 cases of pertussis recorded per year.

This very contagious infection is spread via droplets expelled during coughing. The initial symptoms of runny nose progress to a severe cough that can take four to eight weeks to resolve despite treatment.

Most mothers receive an adult version of this vaccine (Tdap) prior to their due date as a preventative measure for the baby. Household contacts may receive it as well.

The DTaP vaccine is administered to infants at the ages of two, four, and six months old. Booster doses are given at 15 or 18 months old, and again between the ages of four to six.

Hib (Haemophilus influenza type b)

Despite its name, this vaccine protects against a different type of infection than the seasonal influenza virus. Infants are particularly at risk for an H. Influenzae infection under the age of three months old, and it can be life-threatening.

This bacteria is usually spread by someone who has it in their nose and throat, but is asymptomatic. Infections that develop within the first week of life are thought to be transmitted from the mother prior to birth.

The bacteria spreads throughout the body, and can cause meningitis, inflammation of the lining around the brain and spinal cord. This may produce seizures. Despite treatment, infants who survive this infection may have permanent hearing loss.

Although other H. Influenza strains exist, the vaccine only protects against “type b.” There are single dose versions of Hib vaccine as well as those in combination with other recommended vaccines. Depending on which version, infants receive doses at two, four, and six months old, or only at two and four months old. A booster dose is recommended after the first birthday.

Pneumoccocal Vaccine

This vaccine protects against 13 of the 93 known types of this group of strep bacteria. Parents may think of “strep throat’ when hearing the name, but pneumococcal infections are completely different. In infants, they can cause a blood infection that spreads throughout the body, and may cause meningitis under the age of three months.

According to the WHO, pneumococcal infections are responsible for 20% of deaths from pneumonia, and 50% from meningitis under the age of two.

The primary mode of transmission is from someone who carries this bacteria in the nose or throat, even when there are no symptoms of illness.

This vaccine is administered at two, four, and six months old, with a booster dose given after the first birthday.

Polio Vaccine

Polio is a disease caused by infection with the polio virus. Illness occurs when this virus in unintentionally ingested from contaminated food, or from direct contact with a person who has this infection.

The virus then multiplies in the throat and intestines, causing vomiting and diarrhea. Even after these initial symptoms resolve, the virus may still be present in the infant’s stool for up to six weeks.

In severe cases, polio can also cause meningitis. In addition, this virus damages the nerves that control muscles. Depending on which muscle groups are affected, it can result in a paralyzed limb or the inability to breathe.

There has been a worldwide effort to reduce polio infections and transmissions over the years by increasing vaccination rates. Due to these efforts, there are only active cases of polio in Afganistan and Pakistan.

Two versions of the polio vaccine are available: oral and injectable.

OPV is the oral, live version. It is the easiest to administer, and special training is not required. Because it contains a weakened version of live virus, there is a slight risk of developing polio from this vaccine. Vaccine-mediated polio occurs in one out of 2.7 million cases of individuals who receive OPV. The virus is also present in the stool after receiving this version, so parents or caregivers with compromised immune systems should not change the baby’s diapers.

In contrast, the IPV is not a live vaccine, and is administered as an injection. This version is most often used in countries where polio has been eradicated, or where there is sufficient medical training. The dosing schedule varies by country, and whether or not OPV has also been administered.

In general, polio vaccines are given at two, four, and six months old, with a booster dose around 15 months. In some countries, a birth dose of OPV is administered, followed by IPV for the subsequent doses. To reduce the number of injections that infants receive at one time, some vaccine companies offer formulations of IPV combined with DtaP, Hepatitis B, or Hib.

Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR) Vaccine

Measles

Measles is a disease that is caused by a virus with the same name. It is responsible for 350,000 worldwide case, and over 140,000 deaths. It is transmitted via respiratory droplets or fluids from one person to another. Once the virus enters via the nose or mouth, it travels to the lungs, then spreads throughout the body via the blood and the lymphatic system.

Symptoms begin within eight to 14 days, presenting as a high fever, followed by the pathognomonic Koplik spots inside of the mouth. Two to three days later, a red rash develops that spreads from head to toe.

During the peak of this infection, cough, nasal congestion, and redness of the eyes occur along with body aches, stomachache and swelling of the lymph nodes.

In the best case scenario, these symptoms self-resolve after a few more weeks. Complications such as secondary bacterial infections, liver inflammation, and appendicitis are possible, however. Encephalitis, inflammation of the brain, may develop after initial symptoms have resolved, causing permanent cognitive disability.

Mumps

‘The mumps virus causes an illness that is spread via respiratory droplets that are either airborne or on objects used by an infected person. After exposure, symptoms of fever, body aches, and loss of appetite develop within seven to 21 days. This is followed by a severe, painful inflammation of the salivary glands that is often apparent as swelling of the lower face and neck.

In most cases, these symptoms resolve within two weeks. Inflammation of the ovaries or testicles, however, can occur in five to 10 percent of cases, resulting in infertility.

Rubella

Rubella, also known as German measles, is a completely different illness than measles. It is caused by a virus that is also spread from person to person via respiratory droplets.

Once the virus enters the nose or mouth, it travels to the lungs where it can access the bloodstream and lymphatic system. A rash develops within one to two days, spreading from head to toe, followed by a fever and painful, swollen neck glands. “Cold symptoms,” body aches, red eyes, and itching due to the rash are possible.

This rash typically resolves within three days, but the other symptoms may linger for two weeks. Complications are in children are rare, but rubella that is transmitted in utero can cause permanent malformations, preterm labor, and fetal death.

The MMR is a combination vaccine that protects infants and children from these illnesses. A first dose is administered at the age of 12 months, and a booster dose is given between four to six years old. Another version that is in combination with the varicella vaccine can be given for this final dose.

Over the past several years, cases of measles and mumps have increased, and outbreaks have occurred throughout the world. For this reason, a dose of MMR has been recommended for infants as young as six months if international travel is planned.

Because the response to the MMR vaccine does not last when given prior to 12 months, a dose is still necessary after the first birthday. Like the rotavirus vaccine, the MMR is a live vaccine. If there are immunocompromised individuals in the home, you should discuss this with your pediatrician.

Varicella Vaccine

Some adults may remember having the “chickenpox” as a child, enduring weeks of feeling unwell plus an intensely itchy rash.

This common illness is caused by the varicella zoster virus, and transmission is either airborne or from skin contact. It begins with a fever, sore throat, and body aches, followed by a rash within a few days. What begins as a small red pimple, becomes a clear fluid-filled blister that later ruptures to form a crusty lesion. This rash can occur anywhere on the body, including the palms, scalp, and inside of the mouth.

Unlike other viral rashes, different stages of a varicella rash can appear on the same area of the body. After about one week, the lesions become dry scabs, at which time they are no longer contagious. Most symptoms self-resolve without complications, but encephalitis and secondary bacterial infections are possible.

Once signs of a varicella infection are no longer visible, the virus is not truly “gone.” It remains dormant within the nerves of the skin, and can resurface later in life when the immune system is not functioning at an optimal level. Varicella zoster, or “shingles,” infections are common over the age of 50.

The varicella vaccine prevents both phases of this infection. Because the absence of naturally acquired “chickenpox” prevents the virus from imbedding into the nerves, future “shingles” is prevented.

This vaccine is typically administered between 12 to 15 months old, with a booster between ages four to six. Like the MMR, this is a live vaccine.

Hepatitis A Vaccine

The hepatitis A virus causes a liver infection with inflammation that can affect children and adults.

Although outbreaks are more common in developing countries, they have become more common in the United States, typically in food-handling establishments. This virus is acquired from unknowingly eating or drinking contaminated food or beverages.

Once ingested, the virus gains access to the liver via the intestines, and causes inflammation. In addition to fever, stomach pain, vomiting, and diarrhea, a yellow hue develops on the eyes and skin. This yellow color, called jaundice, occurs because the liver cannot process the byproduct bilirubin properly, causing it to accumulate throughout the body.

Hepatitis A gradually improves, and symptoms resolve over the course of weeks to months. If fluid losses from vomiting or diarrhea are significant, hospitalization may be necessary. Unlike other types of hepatitis, the hepatitis A virus does not cause permanent liver damage. Complications in infants and children are rare, and a full recovery is the norm.

The vaccine that protects against hepatitis A is typically administered as a two dose regimen at ages 12 and 18 months.

Influenza Vaccine

The influenza virus is a common cause of respiratory infections that occur during cold weather months. It is one of the most common illnesses in infants and children under the age of five, many of whom require hospitalization.

Influenza types A and B are the most prevalent types, but there have been outbreaks of other versions over the years (i.e. H1N1).

These viruses are transmitted via respiratory droplets that are airborne or on surfaces. One to two days after exposure, symptoms develop, including fever, chills, body aches, runny nose, cough, sore throat, and diarrhea.

Untreated, these symptoms can linger for seven to 10 days. Although the symptoms may resolve without complications, some children may develop pneumonia, dehydration, or brain inflammation. An estimated 600 children died from influenza infections during the 2017-2018 flu season.

An injectable influenza vaccine is offered each year, and updated based on the viral strains that are expected to be problematic. It is recommended for ages six months and older. Under the age of eight, two doses are necessary during the first year a child receives this vaccine to help boost the immune response. These two doses are administered four weeks apart.

Because influenza viruses mutate frequently, an additional vaccine is recommended yearly.

Should I Vaccinate my Baby? Why/Why Not?

While the decision to vaccinate your infant is a personal choice, there are a host of reasons why it is a good idea.

Vaccines protect your baby against many infections that can be life-threatening or have longterm complications.

Certain vaccines, such as the Hib and Prevnar, reduce the need for antibiotics by preventing some of the illnesses that necessitate their use. Other vaccines reduce illness severity and the likelihood of hospitalization. The hepatitis B, MMR, and varicella vaccines prevent future sequelae that can result from such infections. In addition, many vaccine preventable illnesses are no longer prevalent because large numbers of the population are vaccinated.

While vaccinations are recommended in most cases, they may have side effects, and parents often have many questions before vaccinating their children. Find information about common vaccination sideeffects here, as well as answers to common questions.

Read Next

- Help, My Baby is Sleepy After Vaccination Shots!

- Baby Got Knot In Leg After Vaccine? Side Effects, Mitigation and Red Flags

Research References

- The Impact of IgG transplacental transfer on early life immunity

- Meningitis in Infants and Children – HealthyChildren.org

- Long-term impact of infant immunization on hepatitis B prevalence: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Rotavirus – Symptoms and causes – Mayo Clinic

- About Diphtheria | CDC

- Whooping Cough (Pertussis) (for Parents)

- Hib Disease (Haemophilus Influenzae Type b)

- Measles: An Overview of a Re-Emerging Disease in Children and Immunocompromised Patients

- Mumps

- Chickenpox Vaccines for Children | CDC

- Flu & Young Children | CDC

Paula Dennholt founded Easy Baby Life in 2006 and has been a passionate parenting and pregnancy writer since then. Her parenting approach and writing are based on studies in cognitive-behavioral models and therapy for children and her experience as a mother and stepmother. Life as a parent has convinced her of how crucial it is to put relationships before rules. She strongly believes in positive parenting and a science-based approach.

Paula cooperates with a team of pediatricians who assist in reviewing and writing articles.